An inside look: The World Food Programme’s data-driven response to hunger during COVID-19

As COVID-19 has progressed, the need for organizations to be able to quickly access and analyze data has only increased. Tableau Foundation has worked with many of our partner organizations as they’ve navigated new challenges, from increased needs to constrained supply chains and limited resource-delivery options.

The World Food Programme, one of our longtime partners, has made considerable investments over the past few years in data infrastructure. During COVID-19, those investments have proven critical in enabling them to respond to this global crisis. And during the pandemic, we made a new $1.6 million contribution to WFP so they could expand their data capacity and serve not just their own programs, but the entire humanitarian sector.

WFP is the world’s largest hunger-focused humanitarian organization, and they knew immediately that the coronavirus would impact their work. “Our most recent analysis shows that a quarter of a billion people could very likely face severe hunger in 2020, due to job losses and loss of remittances in populations that are already vulnerable” says Enrica Porcari, WFP’s Chief Information Officer.

Many of these communities depend on humanitarian support. With demand increasing so dramatically, WPF recognized there was a risk that existing programs might not be able to meet it. WFP, though, has found innovative solutions to step up its support for the entire humanitarian community to ensure communities have the support they need, even as the crisis evolves.

A global response to a global pandemic

What’s enabled WFP to keep two steps ahead of the pandemic is data.

WFP operates in around 83 countries, and visibility into the conditions on the ground in each community they serve is essential. “When COVID-19 started, it was very difficult for us to have a sense of how big it was going to get,” says Pierre Guillaume Wielezynski, Digital Transformation Services Chief in WFP’s Technology department. But WFP’s investments in data and analytics infrastructure in recent years have set the organization up to remain responsive in times of uncertainty, when quick insights and decision-making are essential.

“We’ve worked very closely with our colleagues across the organization to develop proven methods for tracking the impact of external events—from natural disasters to conflicts—on food security,” Wielezynski says. WFP was able to deploy that same data-driven methodology to rapidly assess the impacts of COVID-19.

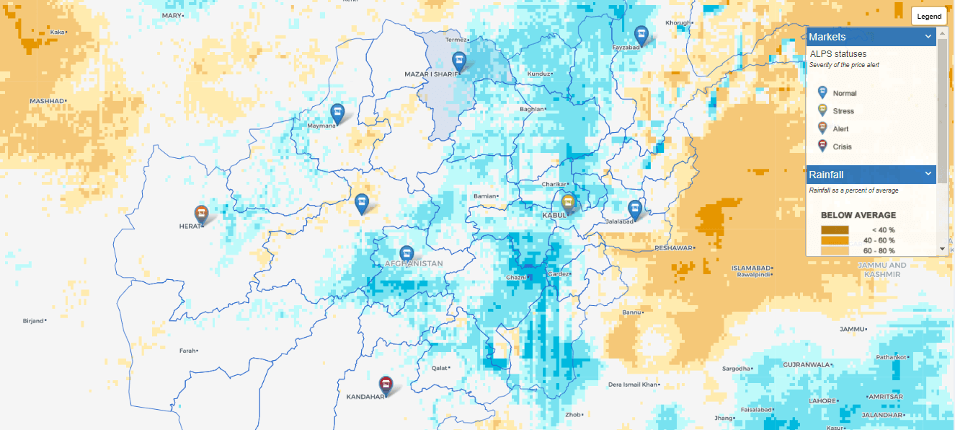

Rainfall and Markets data overlaid for Afghanistan in VAM’s DataViz

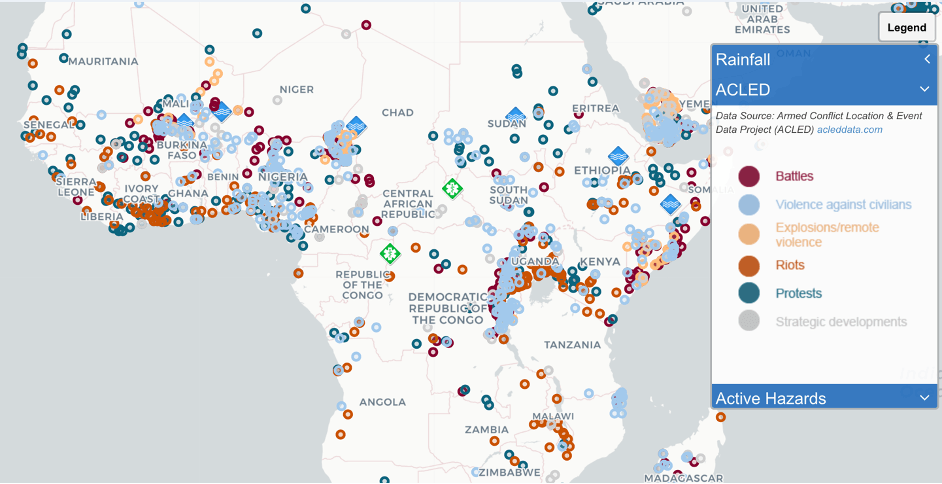

A part of this data backbone is the Vulnerability Analysis and Monitoring (VAM) unit made up of a network of analysts around the world that collect up-to-date data on a variety of metrics that impact food security in a community. VAM oversees data spanning rainfall and vegetation conditions, conflict, hazards and even the world’s largest public market price database, to name a few. With over 100 active dashboards accessible through VAM’s DataViz, the network uses Tableau to communicate crucial information that can inform response.

Powered by Tableau, VAM also compiles data on economic and social circumstances in a community that could affect food security, providing a snapshot of conditions on the ground. Staff can collate this data with near real-time operational updates from WFP’s robust supply chains, allowing them to anticipate disruptions resulting from the pandemic to ensure vulnerable families receive the support they need.

WFP staff track hazards affecting food security using VAM’s DataViz powered by Tableau.

Leading with data

As the pandemic has progressed, this access to data has proven even more essential to the way WFP operates. “We’ve had to really rethink the way we do things if we can’t have boots on the ground in communities, and we’re facing huge challenges in the logistics of delivering resources to people,” Porcari says. WFP’s digital transformation over the last few years has brought data out of silos and made it broadly accessible across the organization to help make faster, better informed decisions.

This has enabled WFP to remain nimble in how it responds to the demands of COVID-19.

“In some cases, we’ve had to take a different approach to n how we assist people,” Wielezynski says. WFP serves some households by delivering essentials like corn, beans, wheat, and oil directly to them. But if the data is showing that the supply chain for these products has been disrupted by COVID-19, WFP can quickly switch to sending them direct cash assistance. Conversely, if a family typically receives cash but the pandemic has inflated local prices, WFP can send them food instead.

For example, having access to this data has enabled WFP to rapidly expand its cash-based assistance in the Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa, where the total number of retailers distributing in-kind assistance almost doubled to 1,300 across the regions. The switch has enabled the organization to scale up support for vulnerable families on the receiving end of the political and economic fallout of the pandemic.

“All of these decisions need to be based on very sound data to justify the switch, but also to design the intervention correctly,” Wielezynski says. “If the market prices are affected and we want to continue giving cash, how much do we give? And how can we continuously monitor these trends?” WFP’s near-real-time insights into the economic conditions that impact food insecurity has enabled them continue supporting families through this crisis.

Building a data resource for the humanitarian sector

Language about supply chains and purchasing power can sometimes obscure the fact that these decisions can be a matter of life-or-death for people. That urgency has driven WFP’s investments in digital transformation both in terms of the data infrastructure and data culture of the organization.

Porcari says what has made responding to COVID-19 possible is not having to start from scratch. “We have had the good fortune and foresight to invest in digital transformation over the last few years, so we have foundational platforms, services and skills that are already very strong. We have strong partnerships that allow us to develop and deploy at speed and scale.”

WFP’s investments in data have even enabled them to build a new resource to support the entire humanitarian sector. The Emergency Service Marketplace is a “one stop shop for the global humanitarian community to access WFP’s supply chain services,” Porcari says. WFP manages an extensive logistics and supply chain network, spanning air, water, and land transportation. During COVID-19, they’ve been able to mobilize this network to support the UN and other humanitarian agencies. “Now they can make a quick, online request to have health and humanitarian cargo shipped to the most vulnerable parts of the world,” Porcari says. “It’s like e-commerce for humanitarians.”

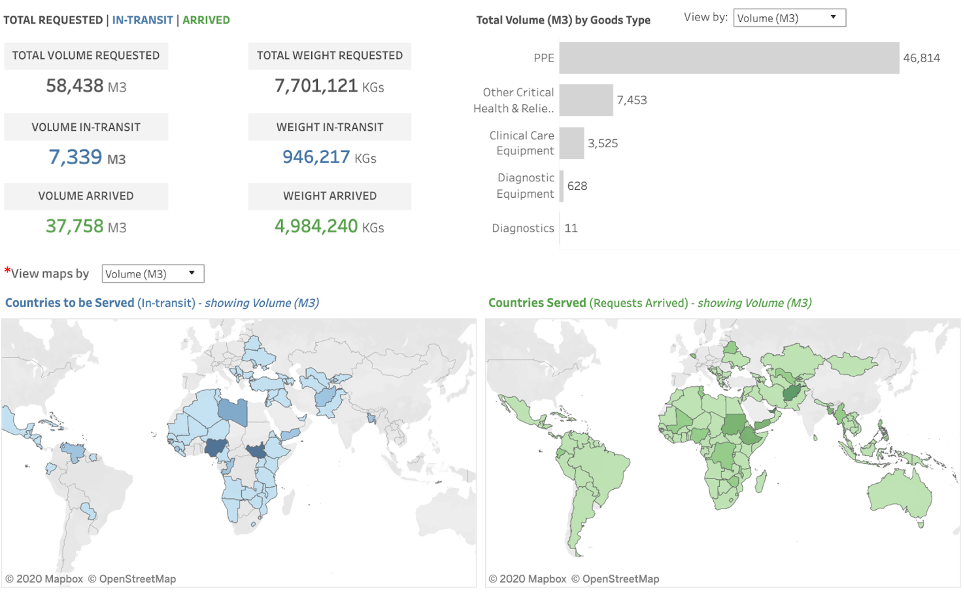

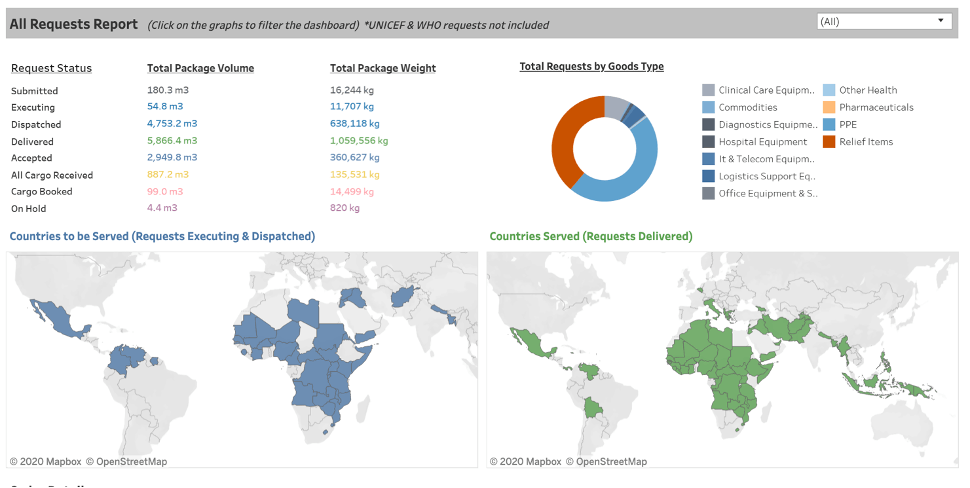

A view of the shipments made via the Emergency Service Marketplace

Rapidly developed in response to the rising demand for assistance brought on by the pandemic, the Marketplace has supported 51 organizations since June, delivering enough humanitarian and health cargo to 265 countries to fill 19 Olympic-sized swimming pools. Because many planes and other transport services were halted, WFP’s tracking system became essential, with Tableau visualizations making it easy for other humanitarian organizations, including WHO, to see where their shipments were in real time and ensure that they made it to their destination.

“It’s a very simple and functional dashboard,” Wielezynski says. “An organization like the UNHCR could use it to request a delivery of masks from China to Mozambique, and then we could optimize the delivery method and show them where the shipment is in transit through the dashboard. The data allows them to recalibrate or reprioritize on the fly, whereas before, they might’ve had to place 20 phone calls only to receive week-old information.”

Staff can track in near real-time the status of their shipments using Tableau.

In a crisis when coordination and timeliness is essential, WFP’s data investments have enabled them to improve the entire aid delivery system for its sector. “This is what you might expect from an Alibaba or from an Amazon, not the humanitarian sector,” Porcari says. “But that’s what our vision is: If Amazon can do it, so can we. We owe it to our donors and the people we serve.”

相关故事

Subscribe to our blog

在您的收件箱中获取最新的 Tableau 更新。